Dr. Avinash Ramtohul

Managing Director, Oracle-MU

Ms. Marion Karanja

Technology Solution Engineering, Oracle Kenya

Martin Waigwa

Technology Solution Engineering, Oracle Kenya

Every Citizen of Kenya, whether individual or corporate, is under the legal obligation to defray applicable taxes to authorities. Representing the main revenue stream of government, it is critical to effectively secure and manage this revenue, especially in the face of challenging global finance dynamics. Changing societal norms and people’s expectations coupled with technological advancement add to the complexity. The Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), established by an Act of Parliament, Chapter 469 of the laws of Kenya, shoulders this challenging task on behalf of the government of Kenya and, among others, assesses, collects, and accounts for all revenues in accordance with the local legislation.

Taxpayers are expected to voluntarily comply with their tax obligations. However, it seems some taxpayers persevere in being non-compliant and exploit various means to evade their tax obligations. As a result, the country still faces the phenomenon of tax evasion leading to a heavy medium to long-term opportunity cost for the country and for the population at large, impacting both – those who are compliant and non-compliant. Edition 1.0 of KRA’s publication Tax Evasion reported having profiled 1,309 individuals and companies with tax loss estimated at approximately KES 259 billion . The publication further reports that over the past few years, financial fraud and tax investigations have revealed sophisticated tax evasion schemes devised by criminals in the supply chain aimed at evading payment of taxes. These criminal schemes take a variety of forms and cost the taxpayer the absolute value of development funds.

The OECD, in 2017, proposed 10 global principles to help fight tax crimes . These encompass the use of legal instruments, leveraging investigatory and seizure powers, and internal re-organization, among others. In fact, these measures can be composed with Artificial Intelligence (AI) to extract and mine information from data sources that can be internal and or external to revenue authorities. Put simply, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines, especially computer systems. The capacity and speed at which computer systems can store, read, combine, and mine information to extract intelligence from various sources is far ahead compared to what the human brain can achieve. AI systems can mine data from tax returns, bank reports, and property statements and further combine such data with information mined from social media accounts to gather evidence that a taxpayer is underreporting her/his income. One could argue that despite the fact that development of AI is unlikely to replace tax advisors in the near future, its benefits in tax preparation and compliance is undisputable. Why would companies otherwise use AI to create models that analyze business trends, simulate risks, and improve their internal efficiency?

Most people may not realize the extent to which artificial intelligence (AI) is utilized in our everyday life. Even those without Alexa and Siri are using AI, be it Google searches, mobile banking, GPS systems, Amazon product recommendations, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Facebook, and chatbots.

So how would this work?

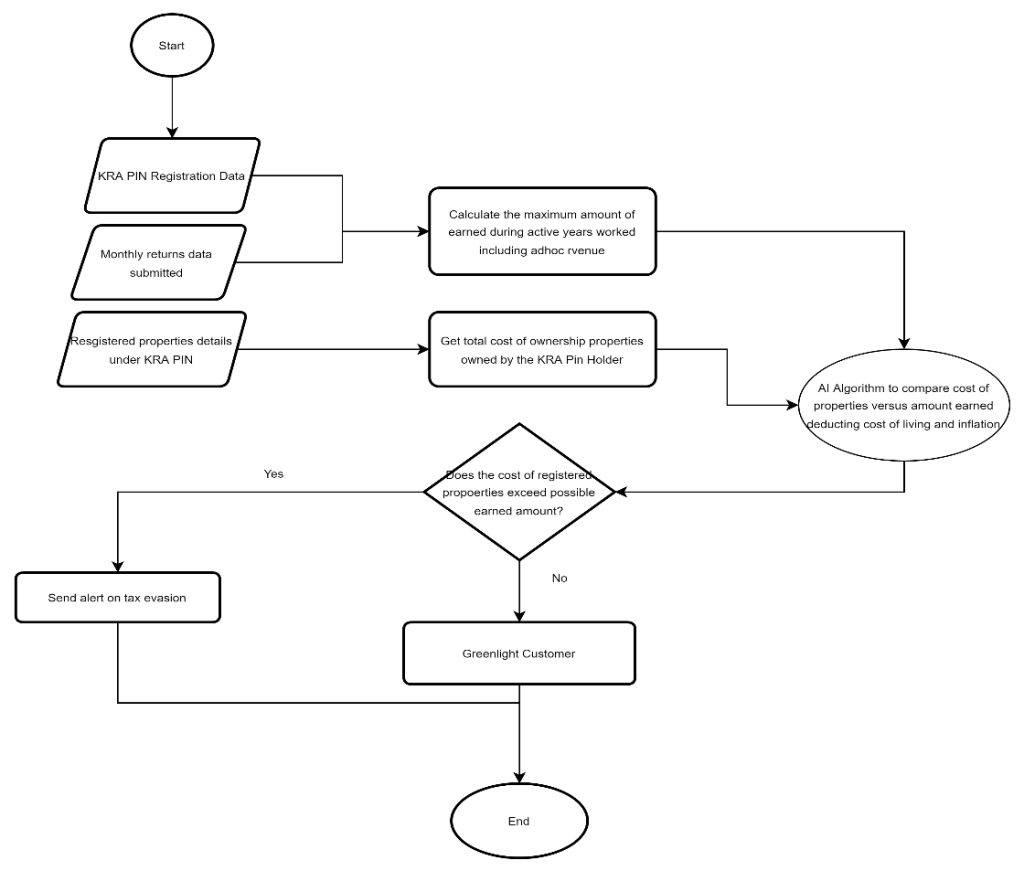

One would be hard-pressed to deny that every transaction we conduct in today’s digital era, whether in the virtual or the physical world, leaves a trace. This would make data a crucial part of the whole process. A simple flow chart below shows how AI would be injected into the systems to alert officials of possible tax evasion.

From the above process flow, a simple example using numbers shows how this would work.

- Monthly revenue of KRA PIN holder as per return submitted last fiscal = KES 6 M. Net revenue after tax at KES 4 M.

- Age of KRA PIN holder = 35

- Property registered under TAN holder by acquisition evaluated at:

Movable Property A registered purchase @ KES 50 M

Movable Property B registered purchase @ KES 22 M

Immovable property registered @ KES 5 M - Total property registered: KES 77 M.

- Calculate maximum number of years worked: 17 years.

- Calculate maximum earned income based on returns: 17 years * 4 M/year = KES 78 M

- Deduct expenses, cost of living, and other factors (inflation), the maximum savings could amount to the maximum salary minus 20%; the maximum possible savings could have been = 80% of 78 M = KES 62.4 M

- Add any other ad-hoc source of revenue (proceeds from the sale of movable/immovable property)

- If registered property value (in this case – KES 77 M) exceeds maximum possible savings (in this case KES 62.4 M) + ad-hoc revenue, then raise a tax-evasion flag.

- If the answer to step 9 is yes, then raise the assessment on KRA PIN Holder.

Steps 4 to 9 would be highly dependent on data mining and use of Artificial Intelligence to get the accurate values necessary to flag the possibility of tax evasion.

Note:

- The lifestyle components can aggregate the purchase made using bank cards, online purchases, and social media posts.

- Payment exchange platforms store all banking transactions.

- While data protection legislation will protect information on consumers, Government authorities may invoke S51(2)(b) and (c) of the Kenya Data Protection Act 2019 under national interest or required disclosure by or under any written law or by an order of the court.

- The above applies to legal entities, including corporate bodies or persons.

Automated and sophisticated Government Revenue Management systems today can map a KRA PIN holder in a multi-dimensional view, nearing a 360 degrees profiling of a person or an entity. These dimensions combine the various aspects of an entity – property ownership (movable & immovable), bank accounts held in the local jurisdiction/declared in foreign jurisdictions, loans repayments, banking transactions, property transactions, electronic purchases, and social media digital footprints, among others, to feed into complex algorithms for automated identification of perpetrators of tax crimes.

The above algorithm is simplistic but can, in a matter of seconds, reveal a large set of KRA PIN profiles that could potentially be evading tax payments giving indicative figures. Much more complexity can be added to the algorithm, factoring in tax payment history, lifestyle index and propensity to evade tax. Such functionality induces predictive capability into automated revenue management systems to crack down on potential tax fraud cases. Empirical evidence is established in the Indian example[1] where tax officials successfully incorporated artificial intelligence into the Goods and Service Tax (GST) administration. The first year of operation unearthed merely 5 cases of “manufactured” invoicing leading to 2 inculpations. A year later, there was a significant increase to reach 1,620 cases resulting in 154 inculpations. The tax department also took organizational measures to curtail any further occurrence of this fraud type.

The use of AI and Big Data approaches have also been formalized and discussed in academic publications. Raikov argues that Developing digital technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and big data, generates new possibilities for improving tax services and proposes a cognitive model for diagnosing suspicious cases that could reveal potential tax evasion. However, these models do not just remain within the realms of academic authoring. Denmark applied AI technologies in tax systems to successfully firm up around 60 cases of tax fraud out of 100 suspicions.

It should be noted that while a lot of focus goes into inducing AI algorithms into sophisticated revenue management systems, authorities should not relegate the need to secure IT systems into a secondary plane. An information security management system is critical to ensure that electronic data is well secured and protected from fiddling by privileged users. The possibility of internal users to collude and reduce tax dues for taxpayers is a possible phenomenon and will definitely deprive the government from revenue. One of the ways of securing the integrity of tax records is to store it on a blockchain network which would keep immutable copies of transaction logs, thus making it technically extremely laborious, almost impossible, to unlawfully alter data to benefit any internal or external entity.

In conclusion, AI embedded within revenue management systems characterizes today’s fight against tax evasion, creating sufficient empirical evidence to support this claim. Leveraging AI to crack down on tax evasion is a global trend, and this approach is increasingly proving to be an effective and cost/time-efficient method to protect government revenue.