Patricia Karamuta Baariu

Landscape Architect/ Lead ESIA&EA Expert

GRI Certified Sustainability Professional

Green Learning Facilitator

The urban environment is dynamic. It is a perpetually evolving complex system comprising human interactions, infrastructure development, political nuances, economic growth, ecological change and technological innovation. It is estimated that currently, over 4 billion people live in urban areas, which accounts for nearly 50% of the world’s population. In Kenya, the urban population is at approximately 30% of the total population, translating to 16.6 million as at the year 2023. Urban areas in Kenya are thriving centres of enterprise, education, social amenities, healthcare and governance. However, they are also characterised by environmental pollution, insecurity, inadequate infrastructure and services including a deficit in decent housing especially for the lower income groups leading to 60% of the urban population in Kenya living in slums and unplanned settlements (UN-Habitat, 2023).

The climate change dilemma

Urban areas in developing countries have experienced the far-reaching impacts of climate change; a trend which is expected to increase, with the World Meteorological Organisation recording 2024 on average as the hottest year in comparison to pre-industrial levels. Closer home, urban areas in Kenya have been experiencing increasingly high intensity floods, rainfall, urban heat islands and extreme dry seasons. These impacts translate to destruction of property and public infrastructure, food insecurity, increased crime rates, internal displacement of people and loss of lives and livelihoods for millions of urban dwellers who are especially vulnerable.

Current interventions

The Government of Kenya (GoK) has formulated policy, enacted legislation, formed partnerships and instituted measures aimed at addressing the impacts of climate change in urban areas. Some of these include enactment of the Climate Change Act, 2016 (Revised Edition 2023), The County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs), and National Climate Change Action Plans (NCCAPs). In addition, and as a precursor to development of these laws and policies, the GoK as a signatory to the Paris Agreement has been submitting Kenya’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The most recent submission is Kenya’s third National Communication (NC3) which was submitted in December 2024.

In addition, non state actors have initiated and/or financed programmes to accelerate progress in climate change mitigation, adaptation and resilience building within Kenya’s urban areas. Some of these initiatives include the Kenya Urban Support Program – The World Bank Group, Cities Alliance Innovation Programme – The Cities Alliance, the Urban Pathways Project – UN-Habitat, The Nairobi City County Climate Action Plan – C40 Cities.

Status of Urban Climate Finance

In November 2024, the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) 29 held in Baku, Azerbaijan brought the world together to secure a new climate finance goal, within a backdrop of adaptation finance needs estimated at USD 215–387 billion annually for up until 2030 and notes with concern the gap between climate finance flows and needs, particularly for adaptation in developing country Parties. In addition, the costed needs reported in nationally determined contributions of developing country Parties are estimated at USD 5.1–6.8 trillion for up until 2030 or USD 455–584 billion per year. (UNFCCC, 2024). The COP 29 outcome called for all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing country Parties for climate action from all public and private sources to at least USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035. (UNFCCC, 2024).

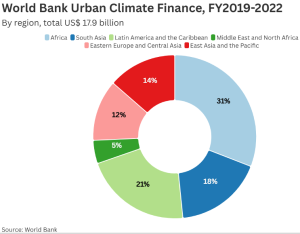

The World Bank Group (2024) in a blog article notes that a limited access to finance is posing a critical barrier to cities’ climate action plans and therefore between fiscal years 2019 and 2022, the World Bank allocated USD17.9 billion to climate finance initiatives in cities and urban systems. This represented almost a quarter of all climate finance channelled by the World Bank during this period. Of this, $8.5 billion, or nearly half, was earmarked specifically for climate adaptation. The article goes on to underscore the interconnectedness of development and climate adaptation finance, especially in urban areas.

In Kenya, there is a financing deficit for climate action related policies, plans and programmes as outlined in some of the international, national and local level commitments. The country requires USD 62 billion until 2030 to support the implementation of NDC targets outlined in its NC3. Its NDCs set out both mitigation and adaptation contributions and, according to the NC3 document, the resource requirements for mitigation activities for the period 2020 to 2030 are estimated at $17,725 Million. Subject to national circumstances, Kenya will bear 21% ($3,725 Million) of the mitigation cost from domestic sources, while 79% the balance of ($14,000 Million) is subject to international support. It is important to note that in the NDCs, there are 13 sectors targeted for action under adaptation. One is directly related to urban development while the other 12 have indirect implications to, and interfaces with, urban development.

Fig 1: A figure representing the distribution of World Bank Urban Finance in regions across the World. Source: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/sustainablecities/how-the-world-bank-is-accelerating-urban-climate-finance#:~:text=Development%20and%20climate%20adaptation%20finance,from%20shocks%20and%20build%20resilience.

Opportunities to bridge the gap

While progress has been made, it is evident that there is a huge urban climate financing gap. This then begs the question: what can urban communities, urban governance leaders, and key experts in urbanisation, climate change, finance and fiscal administration do? Firstly, collaboration, partnerships and cooperation among diverse groups is critical. Collaborations that will effectively tap into the financing available in MDBs, the private sector, local banks, saccos and other financial intermediaries as well as innovative financing model opportunities presented by the carbon markets and carbon taxation.

Secondly, public participation and involvement of urban communities to pursue locally led climate change adaptation models which prioritise the needs of the most affected persons. Thirdly, leveraging on technology and innovation to offer alternative cost-effective methodologies and materials aimed at adaptation and resilience building. Finally, investing in Nature-Based Solutions. While further research is needed, Nature-Based Solutions have been described as more cost-effective for climate change adaptation in comparison to purely engineering solutions. In addition, these solutions come with other social benefits such as improved health and well-being for urban dwellers, increased opportunities for recreation, opportunities for participating in nature-based enterprises and localised environmental control.